About Justine

“…fear not, for I am with you; be not dismayed, for I am your God; I will strengthen you, I will help you, I will uphold you with my righteous right hand.”

Isaiah 41:10 (ESV)

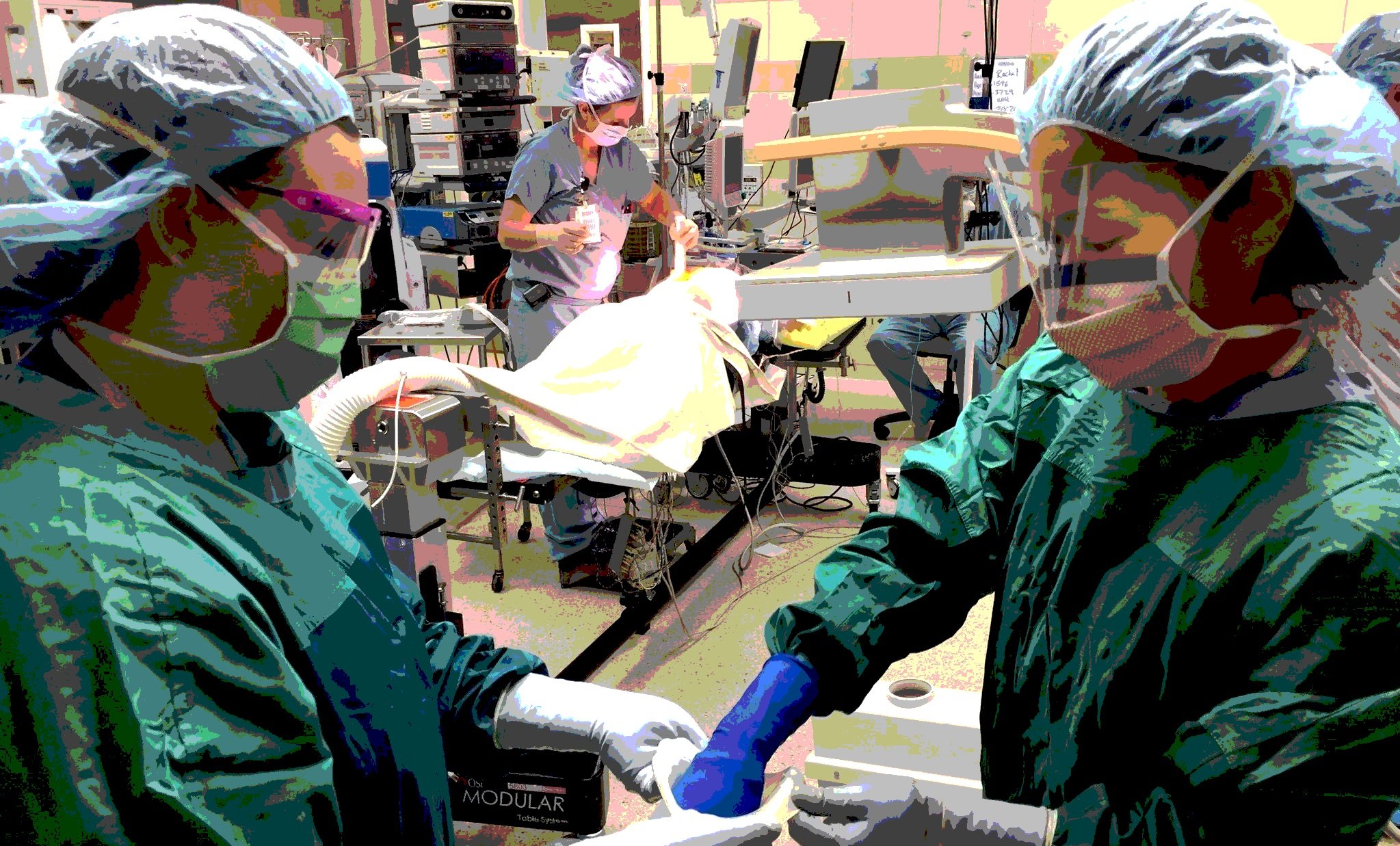

Justine is a DNP Surgical First Assistant on a High-Risk Cardiothoracic Surgery team with her role being mostly focused on the operative phase of care. Justine brings ten years of clinical experience, with four years in an advanced capacity role, focused on perioperative practice. Justine has shown a commitment to advancing her nursing education by obtaining a master’s degree with an acute care focus and by achieving certification as a Certified Registered Nurse First Assistant (CRNFA). Justine has spent the entirety of her career in the perioperative setting, starting as a staff scrub nurse and rising to a full-time first assist focused on cardiovascular surgery.

Throughout her career, Justine has sought out formal and informal leadership roles, including an instructor (and then director) of the new-grad BSN perioperative residency program, member of the multi-disciplinary surgical safety committee (SSC) and serving as a ‘member-at-large’ on the surgical risk review committee, which evaluates, discusses, and has final authority on all high-risk cardiovascular surgery procedures as defined by the STS scoring standards.

In late-2018, Justine joined the prestigious Mayo Clinic Faculty Research Experimentation Practice in the Department of Complex Gastrointestinal and HPB surgery, where she has assisted on experimental open surgeries involving complex pathology, connective tissue disorders, and general anesthesia mitigation.

Justine obtained her DNP from Grand Canyon University in 2022 and maintains the institution’s commitment to Christianity as a vehicle for students to reach their fullest potential through involvement in fundamental biblical principles, living a life of Faith, and exploring service opportunities to utilize functional skills in the spirit of Christ. She has participated on five surgical missions overseas focused on bringing advanced cardiovascular surgical procedures to impoverished countries with lack of sustainable surgical services.

In late-2020, Justine was hand-picked to join the high-risk cardiovascular surgical team as a First Assist - a multi-disciplinary team of both Cardiothoracic and Vascular surgeons at a top-tier research institution that takes on the most challenging cases, many of which involve pathologies of the aorta. Additionally, the team operates on patients with underlying connective tissue disorders, patients with multiple co-morbidities and others who have a very high operative mortality score using the STS modeling.

Justine on First-Assisting in Cardiovascular Surgery:

High-Stakes Cardiovascular Surgery is like nothing else in medicine. You have some of the most talented practitioners in their fields all come together at one table (literally) to put forth all of their experiences, training and mental fortitude to try and help patients with the most critical diseases affecting the heart and vascular system. I always tell people that I didn’t choose Cardiovascular Surgery; Cardiovascular Surgery chose me. You need a calling to be a high-performer in those rooms. It will test you beyond your own perceived limits - physically, mentally and emotionally. The futility of pumping a chest on that table until you can no longer feel your hands, or massaging a heart until the numbness becomes your rhythm is heartbreaking. However, the exhilaration of bringing patients through some of the most brutal and invasive cases and seeing them do well is what makes all of the heartbreak worth it. There is a ‘fraternal’ bond between those who work in the operative field in high-stakes cardiovascular surgery that only we can relate to.

What drew you to the Operating Room and specifically High-Risk Open Aortic Surgery as a sub-specialty of your institution’s Division of Cardiovascular Surgery? I have always been interested in Cardiac Surgery and that was in large part to my mom, who was a Registered Nurse and was the Lead Scrub Nurse for the legendary Dr. Michael DeBakey at Houston Methodist for nearly a decade. She scrubbed-in and assisted on some of the most ground-breaking cardiac surgeries at that time, which provided a good amount of the foundation that modern cardiac / aortic surgery is based on. To this day, I still love hearing about the different techniques that were being pioneered at that time, including things like DHCA, clamp-and-sew techniques, dacron grafting, and reperfusion techniques. High-Risk Aortic Surgery was a natural extension of the work she did and I like being part of that continuum for patients today that undergo these huge life-saving procedures today. I like the intensity that comes with being part of a highly-specialized surgical team where we have very high operative volumes ‘as a team’, which I believe is essential to achieving great results.

I also really enjoy the multi-disciplinary aspect of open aortic surgery where our cardiac surgeons / team get to work alongside our vascular surgeons / team. Many of our large open cases have 8 - 10 hands operating simultaneously and when you have the privilege of working with the same talented surgeons and FAs day-in-and-day-out, you really get to feel the magic that surgical teams strive for, which is that of a well-organized and choreographed symphony.

What do you most enjoy about first assisting in high-stakes cardiac surgery? I think the patient population we deal with gives me the most gratitude - we deal with very sick patients who have often been denied operative intervention at other institutions. I love the ‘continuum of care’ that being a DNP First-Assist affords - I participate in everything from pre-op consultations to perioperative care to post-op (I serve on the CVICU Code Team one night per week). I love the intensity of cardiac surgery - everybody in that room is an A-Player and those that aren’t are quickly uncovered and moved to other teams. There is nothing better than having a patient come in near- or in clinical death and helping them walk out of the hospital with a new lease on life.

What are your ‘rituals’ prior to a big cardiac case? I very much believe in consistency so I always get 7 - 8 hours of sleep the night before. I arrive very early to do any last minute review of case notes, and then we meet as a team for about 30 min prior to scrubbing-in. I eat the same breakfast every morning, which is high in protein (eggs with avocado) - it is super important to maintain energy and focus for our cases with most lasting 10+ hours. I always take 5 min prior to scrubbing to pray in one of our private rooms - I pray for the patient, for the skills of our team, and for myself. I always use the same loupes and headlight - I also use a sweatband that goes underneath my headlight as I tend to perspire quite a bit under the hot lights. I put a piece of tape over my mask to prevent fogging, then put on my loupes and do my 5-min scrub. ‘Surgical ergonomics’ is so important in long cases because you are so focused on the field, you forget about many things, including how much strain you may be putting on your neck and upper back. As I have gotten older, I definitely feel it that night so I am much more conscious of these types of things now than I was 5 years ago.

When I enter the room, our surgical tech is always ready to glove-and-gown me. I double-glove with 6.5 Ansell bright green indicators as the first layer and 6.0 Ansell light-touch gloves over. I prefer a cloth surgical gown as it provides more ventilation. I always walk-through the draping and prep with the lead scrub nurse, surgical tech and circulator so that when the surgeon(s) enter, we are ready to ‘time-out’. I always make sure the table is at the appropriate height for the surgeon - being 6’1”, I usually have to get a step-stool for our surgeon.

Since we have a very strong aortic program, we often get patients flown in from secondary and tertiary facilities that are in or near asystole. In these situations, there is no time to waste. It’s all about getting that patient on the table ASAP, ensuring somebody is maintaining circulation via closed compressions, and getting them prepped and draped to get them on bypass.

What are some tips for being an effective First-Assist in cardiac surgery? Cardiovascular surgery is one of the most unique specialties given the high-acuity and how things can go downhill so fast. I always follow the tone of the surgeon and try to be the best ‘servant’ as possible. As long as you always frame each case and prepare for it with the ‘best interest of the patient’ in mind, then becoming an effective First Assistant will come with practice, experience, case volume and building trust with our Cardiothoracic and Vascular surgeons. Being mindful of the standard is extremely important. Our surgeons make it clear from day-1 that excellence is the expectation, not the aspiration. This type of mentality drives me to take care of my own personal well-being (you can’t perform well in marathon cases if you are not in tip-top physical and mental health), understand the importance of case preparation (patient presentation, history, operative approach, operative steps, potential complications at each point, etc.). Before a big open aortic case, I always schedule time with the attending Cardiothoracic and Vascular surgeon to walk through the procedure and find diagramming out the most critical pieces to be an invaluable exercise to visualize the anatomy. I also think reading case studies from around the world are really helpful - they always provide invaluable perspectives on different presentations, approaches, techniques, and complications.

Anticipation is everything:

You have to do your homework - every patient is different and this can greatly affect the approach and potential complications. There is nothing more beautiful than being able to operate with very few words spoken - that’s when you know you have a great team - it just flows in a way that makes the team seem as one.

Keeping Eyes Focused on Operative Field:

Your hands will inevitably move when your eyes look away. If the surgeon is performing an anastomosis and you are holding the vein with forceps, a momentary look away to find the suction, for example, will move the vein. Either keep both eyes and hands focused on the field or remove them. Unlike social settings where eye contact is expected, it should be avoided and can be dangerous while operating. When communication is necessary, it should be done without averting the eyes from the field. The message can then be relayed through the appropriate channels - often times to a second assist and then to a scrub nurse.

Prioritizing the Surgeon’s Aperture:

The attending surgeon’s and first assistant’s visual perspectives are different, as each one views the field from a different angle. As the FA, I may have to adjust my body to obtain the appropriate visual field to assist the surgeon. Given this, it is essential that I be familiar with the various steps of the operation and the goals of each step. For example, when performing aortic cannulation for bypass (CPB), the surgeon will need to place a stitch on the aorta. To assist with exposure and facilitation of this step of the operation (via suctioning or tissue retraction), I need to lean forward from the left side of the table toward the head and peer under the shelf of the divided sternum. This allows me to see what the surgeon sees.

Attitude and Thick Skin:

I come with a positive attitude to every case - there is no need to bring up negative topics or provocative conversation during a case. I never say, “I can’t”. Cardiac surgeons are under tremendous stress during high-intensity cases especially if things are not going well. Yes, there are certainly times when I’ve been told in no uncertain terms that I need to do better - it is not a time for debate and I don’t take it personally - I just listen and move forward. It’s all about the patient.

Predictable Movements:

There is nothing more distracting to a surgeon than having a First-Assistant who is jerky and unpredictable. It is imperative as a First Assistant to make sure the surgeon can maintain complete focus on the operative field.

Both Hands Need to be Operating:

I learned very early on that a First-Assistant needs to always be using both hands to move the procedure forward. This may mean retracting with one hand and helping with a suture with the other. In cases of extremis, I have had one hand performing open cardiac massage, while the other hand is helping suture a wound in the heart.

Communication:

Communication in cardiac surgery is so key - there are a lot of moving pieces and the best way to align everybody is through closed-loop communication. If the surgeon asks for the defibrillator paddles at 20J, I will always hand them over and verbally close the loop with, “Internal paddles at 20J, doctor”. I expect this type of communication from everybody in the field. I also expect those not in the field to keep the side chatter down. No matter how close I am with a surgeon, demonstrating respect through communication is key.

Utilize Universal Hand Signals to Minimize Verbal Distraction:

Simple, silent hand signals to the Second Assist will keep things quiet and peaceful. Use three signals routinely:

Scissors are the straight index and middle fingers coming together and apart;

Forceps are the index fingertip and thumb tip brought together repeatedly;

Needle holder (with suture) is a closed hand moving with a slight twist repeatedly, as if placing a stitch.

These three hand signals are universal and lessen the verbal sensory input at the table

Staying Poised during Crisis:

We deal with intraoperative complications often and the best way to behave is by staying poised and methodical. If a patient is off-pump and goes asystolic, I am often the one tasked with internal cardiac massage while anesthesia pumps the meds, and perfusion is furiously trying to get us back on bypass. If we can get the patient back to a shockable rhythm, I usually assist with internal defibrillation. My role is to do whatever is necessary to get the patient back on-pump or initiate acute resuscitative measures.

Maintaining Objectivity:

I care about each of our patients deeply and never forget that beneath those drapes is somebody’s mother / father, brother / sister, friend, son / daughter - it is never ‘a case’ to me. That being said, high-stakes cardiac surgery requires a level of emotional detachment to perform at the highest level. I always set that expectation with patients and their families during pre-op consults - the notion that the team ‘seeming cold’ is best for the outcome. You can still be compassionate without getting vested in the emotional needs of the patient and his / her family. There is nothing more gratifying than being able to meet with a family after a huge procedure and see the gratitude that they have for our team’s efforts with the ultimate reward seeing that patient walk out of the hospital.

Most Dreaded Moments:

To this day, the most dreaded moments I face are not actually in the Operating Room. It is getting a ‘stat page’ that one of our post-op patients has arrested in the CVICU. Our CVICU rooms are ‘hybrid rooms’ so we often will re-open right there. Maintaining order in the CVICU when you’re furiously scrambling to get a patient’s chest back open due to tamponade or cardiogenic shock is challenging. Once again, it comes down to communication and protocol. We have a great support team in the CVICU who are well-trained in resternotomies so knowing you have that support is huge. I immediately begin a quick scrub so that I can be gloved-and-gowned in a matter of a minute. I expect all instruments to be ready so that when the attending arrives, we can quickly clip through the sternal wires and get to the heart to begin massage. Another challenging component for me in CVICU resternotomies is that the family is often close by and can hear / see the chaos. I have to zone that out to be efficient in my actions as every second counts when a patient is not getting perfusion to the brain.

Favorite Procedure(s):

I love Open Aortic Surgery - it is the highest stakes as the physiology of the body is so interconnected and usually requires a ‘maximally-invasive’ approach for exposure. You have to manage not just the pathology, but also the neuro motors, renal function, and intestinal perfusion. Open Thoracoabdominal Aortic Aneurysm repairs are very challenging, especially with patients that have very friable aortic tissue due to underlying pathology like Marfan’s syndrome. It is a maximally-invasive surgery where you need a huge amount of exposure, which often requires removing ribs and using big self-retaining retractors. The pressure during these cases is so high especially when you clamp the aorta knowing that every second you are cross-clamped, the kidneys and spinal cord are not getting perfusion. The procedures that we do the most include:

Open TAAAs: These patients often suffer from underlying connective tissue disorders like Marfan Syndrome, EDS, etc.

Redo Open TAAAs: We often will do reoperative TAAAs for patients that may have had the original one done a while back or are experiencing complications following their initial repair, which may include contained ruptures, infected grafts, extension of the diseased tissue or malperfusion.

Concomitant Aortic Surgery: These are probably the most challenging cases. We have one of the highest volumes of cases repairing Aortoesophageal Fistulas (AEF) secondary to TAAAs. These are massive and high-risk undertakings where we have to get source control of bleeding in the chest, repair the aorta, debridement of necrotic tissue / drainage of purulent fluid, and then either do a primary repair of the esophageal perforation or (more than likely) perform a radical esophagectomy - contamination control from esophageal leakage is extremely challenging - these types of surgery often last in upwards of 12 - 14 hours.

Aortic Trauma Surgery: Whenever a patient has suffered a major injury to the chest (especially blunt thoracic injury) or penetrating injury from a GSW or stab wound, there could be aortic involvement in the form of transection or laceration. For patients that make it to our L1 Trauma Center and can be successfully resuscitated (as often spiral into full cardiac arrest) with an identified injury to the aorta, our team will be called in to help with the long-shot repair. These are extremely challenging cases as the blood loss occurs so fast that it becomes a race to repair the aorta to limit irreversible damage due to malperfusion of the brain, kidneys, intestines and spinal cord.

Most Devastating Case:

The most devastating case I've been in was a 3rd time re-do sternotomy, re-do coronary artery bypass. I taking vein and had a really difficult time even finding one piece that was suitable for a graft because the guy's legs had already been cut during his previous case, which I had first-assisted on two years prior. I actually got once piece that was only about six inches long which was JUST far enough for the RCA graft we were there to replace. We ended up trying to dissect his heart out of all of the adhesions which took forever. We were trying to stay inside the pericardium without stripping layers off the heart. We go into the RA multiple times and it was damn near impossible. We never even made it all the way around the left side of the heart for fear we would damage his previous vein grafts and LIMA that remained patent from the previous operation. We got the graft sewn on but the bleeding was absolutely horrendous. We gave every blood product under the sun in addition to K-centra and Factor 7. We never got control and he spiraled into cardiogenic shock, VF and then Asystole. We applied 12 internal defibrillations and then I massaged his heart for nearly 45 min as the attending attempted to control the bleeding and try anything to get him off the table. The case was over 15 hours with a terribly disappointing ending but there was truly nothing more we could do. We told the guy pre-operatively that the RCA lesion found on cath was likely not the culprit of his chest pain and that he may not make it off the table due to the level of adhesions. We had done his second sternotomy case too and the operative notes outlined how bad his adhesions were. He wanted the surgery though and insisted on undergoing the operation with full knowledge of the risks. It was a sad case but we tried absolutely everything and nothing worked. Since this was my second time assisting on his surgery, I had gotten to know both him and his family quite well, which made the adverse outcome all-the-more painful. This case made the emotional detachment described above more important to me as the pain of this ‘Failure-to-Rescue’ all-the-more painful.

Loss of a Patient on the Table:

There is nothing worse than fighting for a patient on that table for hours and then ultimately losing them during surgery. I still remember a complex re-do Bentall with awful adhesions and we just could not control the bleeding. We initiated a MTP, gave unit-after-unit of Factor-7 and could not get him off the table. It was nearly a 14-hour case and I just remember the surgeon and I massaging that heart for nearly an hour. It is an awful feeling, but I take solace in my Faith and knowing that we did everything we could. It never gets easier and if it did, I would not be in this field anymore.

Speaking to the family after an Adverse Outcome:

After an adverse outcome, I always accompany my attending to talk to the family - this never gets easier. Walking into that room and telling a family that we lost their loved one on that table is such a horrible feeling. I have learned it’s ok to say, “I don’t know” or “I am sorry”. People react differently to this type of news and you have to respect that by not using jargon, showing humility through honesty, and giving them the space and support they need to process such devastation. Many times (esp. after a prolonged resuscitation on the table), I am covered in blood and sweat. I always take the time to clean myself up prior to speaking with the family - it’s a little thing, but so important given the magnitude of the news.

Relationship with my Surgeons:

I socialize with my bosses but always keep things professional. I joke around with them outside of the Operating Room but always go with whatever tone they set for the room. It is easy to tell what kind of mood they are in and I respect that in the OR. I say ‘yes, doctor’ and always have respect for the challenges they face during cases. I never say “I can’t” during a case. If they are asking me to do something or expose something that is difficult, I just always try and always use both hands to at least attempt to do what they are asking. As mentioned, I have an empty hand and never stand there doing nothing. There is ALWAYS something I can be doing to help them identify, expose, find, sew etc. If it is a new type of case and I don't know exactly what instruments to use to help them, I give it my best shot - I would rather have something ready then be completely empty handed. My job has one purpose to the surgeon(s) during a case - it is to make their job easier, so do whatever it takes to make that happen is what I am willing to do.

If successful patient outcomes are the ultimate gratification (as they are), then winning the respect of our Cardiothoracic and Vascular Surgeons has to be second. They are under so much pressure that to hear they want / need you for these high-risk cases is so gratifying. It means that I have lived up to their expectations and have collaborated with them ‘as a team’ to achieve a great outcome.

First-Assisting in Cardiac Surgery is not for everyone. The stakes are never higher and the demands never greater, but knowing that you are a valued and trusted member of a dedicated team of a high-performing surgical team is an incredibly rewarding experience. It does not come for free - the technical knowledge, preparedness, and emotional temperament is essential to going from good to great.